In a breakthrough that blurs the line between biological intelligence and computational modeling, researchers from Dartmouth College, MIT, and Stony Brook University have built a brain model so biologically faithful that it learns exactly like lab animals — despite never being trained on animal data. Even more striking, the model exposed a previously overlooked pattern of neuron behavior that scientists later confirmed in real brain recordings.

The work, published in Nature Communications, marks a major leap in biomimetic computing and could reshape how we study cognition, disease, and future neurotherapeutics.

A Brain Built From First Principles — Not Data

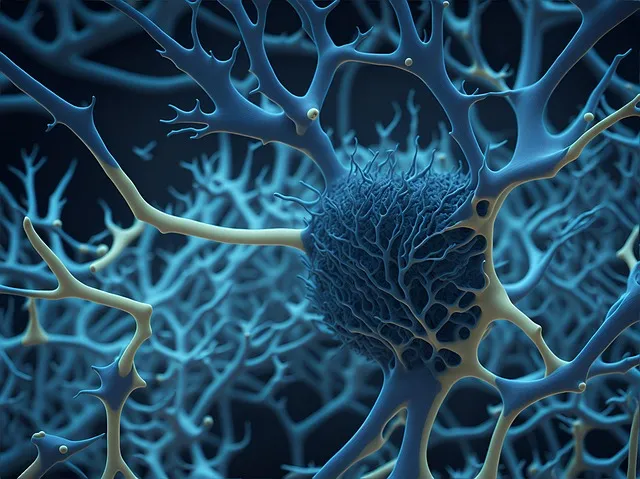

Unlike typical AI systems trained on massive datasets, this model was constructed from scratch to mirror the real brain’s architecture and chemistry. It simulates how neurons connect, compete, synchronize, and communicate across regions such as the cortex, striatum, and brainstem. It even includes a “tonically active neuron” system that injects acetylcholine‑driven noise — a biological mechanism that helps animals explore and learn.

When tasked with a visual categorization challenge previously given to animals, the model learned with the same uneven progress, produced nearly identical neural activity patterns, and matched behavioral performance.

Dartmouth’s Richard Granger, senior author of the study, called the similarity “shocking,” noting that the model generated its neural dynamics independently — only later compared to animal data.

A Surprise Discovery: The ‘Incongruent’ Neurons

The model didn’t just replicate known biology — it revealed something new.

About 20% of its neurons consistently predicted errors, firing in ways that pushed the system toward incorrect decisions. Initially dismissed as a modeling artifact, these “incongruent neurons” turned out to exist in the real animal data as well — simply unnoticed until the model highlighted them.

MIT neuroscientist Earl K. Miller suggests these neurons may serve an adaptive purpose: occasionally breaking the rules to help the brain adjust when environments change. Other studies at the Picower Institute have shown that humans and animals sometimes rely on similar exploratory strategies.

A Platform for Future Neurotherapeutics

Beyond scientific insight, the team envisions practical applications. Granger, Miller, and co-author Lilianne Mujica-Parodi have launched Neuroblox.ai, a company developing the model into a platform for simulating brain disorders and testing interventions — including drugs — before moving to costly clinical trials.

Miller describes the goal as “a more efficient way of discovering, developing, and improving neurotherapeutics,” using biomimetic simulations to accelerate early-stage research.

A Model That Keeps Growing

Lead developer Anand Pathak designed the system to integrate both microscopic neuron‑to‑neuron interactions and large‑scale brain rhythms — a dual approach many models avoid. The team continues to expand the model with additional brain regions, neuromodulators, and behavioral tasks, aiming for an increasingly comprehensive digital nervous system.

Supported by the Baszucki Brain Research Fund, the U.S. Office of Naval Research, and the Freedom Together Foundation, the project signals a future where computational neuroscience doesn’t just imitate biology — it helps uncover it.

![[Expert Guide] The Latest Innovations in Digital Tools: How to Stay Ahead in the Tech Game](https://thecrazythinkers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/tamlier_unsplash_-5BExpert-Guide-5D-The-Latest-Innovations-in-Digital-Tools-3A-How-to-Stay-Ahead-in-the-Tech-Game_1681918074-768x353.webp)

![Revolutionizing Warfare: How WWI Technologies Changed the Game [Infographic + Expert Tips]](https://thecrazythinkers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/tamlier_unsplash_Revolutionizing-Warfare-3A-How-WWI-Technologies-Changed-the-Game--5BInfographic--2B-Expert-Tips-5D_1681910815-768x353.webp)

![Unlocking the Power of Social Media Technology: A Story of Success [With Data-Backed Tips for Your Business]](https://thecrazythinkers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/tamlier_unsplash_Unlocking-the-Power-of-Social-Media-Technology-3A-A-Story-of-Success--5BWith-Data-Backed-Tips-for-Your-Business-5D_1683142110-768x353.webp)

![Revolutionizing Business in the 1970s: How Technology Transformed the Corporate Landscape [Expert Insights and Stats]](https://thecrazythinkers.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/tamlier_unsplash_Revolutionizing-Business-in-the-1970s-3A-How-Technology-Transformed-the-Corporate-Landscape--5BExpert-Insights-and-Stats-5D_1683142112-768x353.webp)